It’s a long way to Nottinghamshire,/ Or to Chiapas, Mexico,/ But you can’t tell me that Robin Hood ain’t real/ Since the Feds caught up with Oso Blanco!/ – The Martyr Index, Oso Blanco

I hope to inspire people to have courage beyond their daily understanding. As we truly have endless love and power within. – Letter from Oso Blanco, 6/4/2019

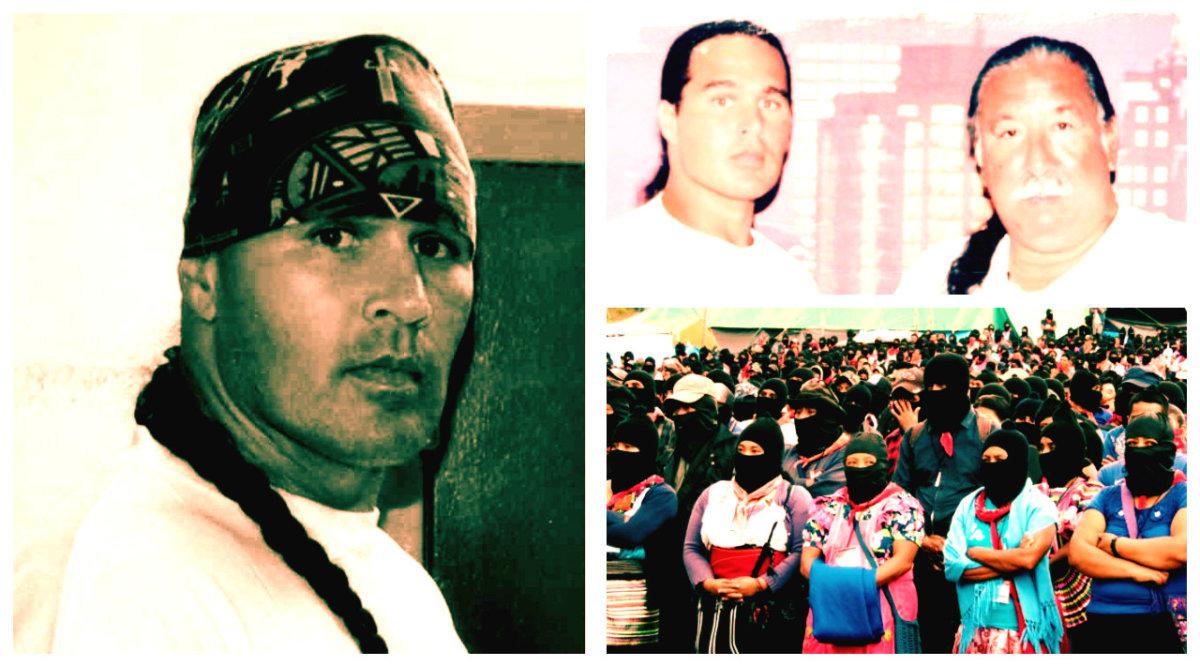

Official sources say that Oso Blanco, to whom the State refers by his birth name, Byron Shane Chubbuck, is responsible for about 20 bank robberies from 1998-1999, all undertaken for the express purpose of aiding the EZLN (Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional/Zapatista National Liberation Army) in Chiapas. Oso Blanco himself puts the number of “robberies” at closer to 50.

The bankers got bailed out. Oso Blanco went to prison.

There’s a satisfying symmetry—I won’t call it poetic justice—in using money from banks to fund revolutionary struggle. Banks are in the business of burying people’s hopes and of destroying their dreams. But the goals of freedom-fighters like the Zapatistas—and like Oso Blanco himself—are to keep hope alive, to nurture the revolutionary dream of a world free from oppression and exploitation. There’s also a crucial difference between pilfering money for selfish interests—be it lining your own pockets or placating shareholders—and expropriating funds necessary to aid in revolutionary societal transformation. The bankers did the former. Oso Blanco did the latter. The bankers got bailed out. Oso Blanco went to prison.

To the Feds, and to local law enforcement, Oso Blanco was never anything more than another greedy, power-hungry thug with a chip on his shoulder and an axe to grind. Grudgingly bestowing upon him, doubtless with no small amount of derisive irony, the moniker “Robin the Hood,” official accounts of Oso Blanco’s actions are designed to make the public question if the funds he expropriated ever made their way to Chiapas.

With the mainstream media’s eagerly proffered support of their lies, the Feds and their pals have painted Oso Blanco as a vain, charismatic, and dangerously manipulative hustler. To hear them tell it, he’s an odd combination of Jim Jones and Scar Face with a dash of Che Guevara for flavor. Even the more sympathetic media accounts paint him as little more than a short-sighted victim of his own inability to lead an honest life and obscure his political motives behind the foggy rhetoric of personal responsibility. While such accounts do provide a brief glimpse into Oso Blanco’s humanity, citing things like his short-lived recording career or his love and talent for art and poetry (he published a book of verse in 2011), they’re predictably heavy on the pathos and light on the politics.

Oso Blanco, above all else, defines himself as a warrior and as a spiritual man who puts all faith in the Creator and for whom indigenous spirituality is paramount. He is a proud sovereign citizen of the Cherokee Nation who is a direct descendant of high-ranking Cherokee War Woman Nanyehi Ward. Among his relatives may be found the leader Dragging Canoe, remembered for leading successful armed opposition to settler-colonialist expansion that European historians would call The Battle of Lookout Mountain. A burning sense of justice and a legacy of militant anti-colonial resistance runs through Oso Blanco’s veins.

This could be partially why, after his initial arrest, he freed himself from State custody and, following a short meal in a motel, went right back to expropriating funds for his comrades in Chiapas in their fight against a tyrannical government. He also made a point of calling a local radio station to challenge the prevailing narrative about his actions and to report on the foul and abusive conditions he experienced and saw there. Even after he was arrested again and sentenced to an additional 40 years of hard time, bringing his total sentence to 80 years, he remained resolute. “I will not be broken in my determination and willpower,” he vowed after he was recaptured, promising that he would continue to support EZLN rebels while “smacking the federal government across their face of hypocrisy.”

This disdain for hypocrisy and dishonesty, though perhaps counter-intuitive to those who are content to dismiss him as another “run-of-the-mill criminal” (whatever that means), is one source of the sincerity that Oso Blanco carries into every personal interaction. A large part of what draws people to him is a combination of honesty with a strong depth of conviction. The past that the mainstream media and the State have flaunted (in their predictable attempts to vilify another revolutionary) is one that Oso Blanco has never denied having. What prevailing accounts also ignore is Oso Blanco’s persistent urge to do genuine good, like supporting Project Share, a local houseless shelter, after he caught his first federal case at the age of 31.

Oso Blanco artwork

His time there was a condition of his parole, but others involved with the project say he went above and beyond in his work there. Cathy Blanco (no relation), then the direct of the project, is a person who, to this day, Oso Blanco credits with always pushing him to do what he knew was right, and to never stop helping people. He talks openly about that first case and about his time in prison, and about his gang activity before and after. He also talks openly about his own drug use, and his involvement in drug manufacturing and trafficking. He describes this period in his life as his leaving “the good path of helping others” to walk instead a “Path of Death.” It was from this Path of Death, insists Oso Blanco, that the Zapatistas saved him shortly after he first became aware of their activities.

That was in Albuquerque, back in 1997. He was watching a protest against human rights violations in Chiapas. A woman who he calls “Gloria” noticed his eagle feather tattoo, and the conversation quickly turned from indigenous struggle in the US to the Zapatistas’ work in rural Mexico. She gave him her card and they parted ways. A year later, Oso Blanco was in Guatemala City looking to score two drums of ephedrine to manufacture methamphetamine. Gloria was there, too, looking to purchase supplies to take to the Zapatistas. Oso Blanco gave her the cash she needed, rented a truck to carry the supplies, and helped to deliver them. He left with only a single drum of ephedrine, and with having seen firsthand the work that the Zapatistas were doing for the people. “When I completely realized those EZLN warriors were not playing games,” he says, “I went ALL IN!” And there’s no denying that’s exactly what Oso Blanco did.

Back in New Mexico, things really began to change. Oso Blanco, then the jefe of a local gang, began instructing his members to give back to their hood, and encouraged them to support, protect, and defend it and the people living there. “Siempre con honor”—always with honor—became the primary driving principle for most of the crew’s members. It was also around that time that Oso Blanco began knocking over banks, expropriating the cash and using the bulk of it to buy necessary supplies to send to Chiapas, setting some aside to support his growing family and to invest in local neighborhood support projects. He would also routinely send plates, napkins, and food to Project Share when the shelter was struggling to keep houseless people fed. And according to the tellers, and to Oso Blanco, each bank job took place in the same way. He never used a gun, and was always polite when asking for the cash, which he also told bank employees would be going to support poor and starving children—referring, of course, to the Zapatistas’ numerous local projects (from thence came Oso Blanco’s sobriquet of “Robin the Hood”).

Among the goods sent to Chiapas were batteries, cell phones, books, military surplus and equestrian gear, fabric dye, vitamins, and antibiotics. Some friends of his who owned a trucking company agreed to help transport the goods. It’s impossible to estimate the total cash value of the supplies, or the amount of the supplies, sent. But the one thing that is for certain is that Oso Blanco would do it all again without hesitation.

Oso Blanco’s personal and political commitments have not wavered, even though the State has done everything it can to break his spirit and silence his voice. As if trying to bury him under an 80-year sentence wasn’t enough, in the initial 17 months he was incarcerated, jail staff gassed, beat, and otherwise abused him on an almost routine basis. It was this routine abuse that Oso Blanco says drove him to escape. While incarcerated at USP Leavenworth, Oso Blanco was denied his right to attend sweat ceremonies with other First Nations inmates until persistent pressure on the prison bosses, coming from inside and outside the walls, derailed the State’s attempt at targeted ethnocide.

In a recent letter from 2019, Oso Blanco briefly discusses being attacked, at times, by as many as 8 guards at once in the SMU (Special Management Unit), and being left in tightly fastened restraints for an excess of 80 hours at a time, which has resulted in permanent neurological damage. In other correspondence he has discussed routine denial of medical care and efforts to frustrate his correspondence with friends, family, and loved ones on the outside as punishment for his refusal to relinquish his identity and submit to State control.

But Oso Blanco does not want pity, nor does he want to be idolized or revered. An anarchist since 1982, he has no interest in being the object of hero worship. “We are [all] heroes,” he insists, “who can help many, many people.” All we need to do is awaken to our own abilities. “We need only to use our energies in positive ways. And focus clearly, for our potential is endless, amazing.” And this, says Oso Blanco elsewhere, “is the true source of revolution: to [achieve] higher consciousness and to keep it.” He wants his story told, not to build his fan-base, but to build revolutionary struggle. For him, his life’s story is proof that it is possible for people to rise above the baser aspects of their nature that capitalism nurtures. He’s been the subject of songs, news articles, and of National Lawyers Guild resolutions in support of political prisoners.

He’ll spend the rest of his life with half a 9MM round lodged in his cheekbone, and he’s got scars on his torso that mark where Feds shot him in the back. It’s easy to read Oso Blanco as an enigma. And, in some ways, he is. This is, in part, because his attitudes and actions cannot be made sense of using the narrow, binary illogic of the capitalist system. Understanding revolutionary action requires breaking with that logic. What’s important to Oso Blanco is that people see that undertaking revolutionary action requires the same thing.

Really, Oso Blanco is no different than we are: he is a person who, recognizing the harmful and problematic behaviors and beliefs that the system encouraged in him, has always strived to transcend those limitations. His story reminds us that we cannot transform society without transforming ourselves. To see Oso Blanco as a singularity is to ignore that we all have a tremendous capacity to achieve radical personal, and societal, transformation—which is exactly what the ruling class wants us to ignore. They want us feeling afraid and isolated, insecure and unaware. Oso Blanco was imprisoned because, when he fought for the Zapatistas, he was also fighting for all of us, and we could very easily find ourselves in his place. There may come a time when the State decides to make any one of us into an example. So, save the ballads and songs, the laurels and the accolades. Like his words and actions suggest, lets show support for Oso Blanco by working collectively to make our daily lives the stuff that revolutionary remembrances are made of. Let’s build struggle however we can, wherever we are—and don’t forget our comrades behind the walls. After all, all we really have is each other.